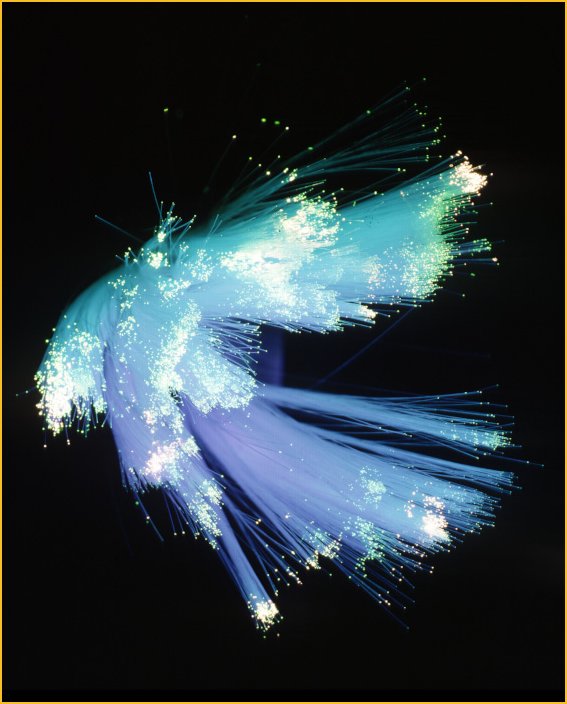

Internet Heading to Light Speed

18 August 2004 by axxxr A new nanotechnology that eliminates network bottlenecks could help create a web surfers' paradise that is 100 times faster than today's internet.

Fiber-optic networks capable of sending information at 10 Gbps or 40 Gbps are being rolled out around the world and under the oceans to connect everyone to everything. But getting information to pass from one high-speed network to another can be slowed by electronic switching technology. The new technology, described in a paper published Aug. 11 in the scientific journal Nano Letters, uses buckyballs glued together by a custom polymer, providing a way to create an optical switch. "Switches and routers do introduce latency," said Karl Lehenbauer, chief technology officer of broadband networking company Superconnect. "If the (data you request) has to pass through 15 to 20 routers, you can see a lag in response," he said. Part of this slowdown is caused by the conversion and reconversion of information from its optical (light) form to electronic data used by switches and routers, according to Ted Sargent, a professor in the electrical and computer engineering department at the University of Toronto. "We haven't been able to speed the scale of (electronic) routers to keep up with the speed of fiber-optic links," Sargent said. The solution, according to Sargent, is to upgrade to optical switches that can forward data at up to 100 times the speed of today's fastest networks. Sargent worked with researchers at Carleton University to develop a new polymer material that could be integrated into optical switches. "You could have an optical switch that directs incoming information to go north to San Francisco or south to Los Angeles as needed," Sargent said. That option would trump electronic alternatives for performance -- the light (and data) would pass through the switch in as little as one-trillionth of a second, according to Sargent. The researchers created a thin film by using a custom-made polymer to glue together nano-sized buckyballs. The gluing process creates a material composed of larger electron-rich molecules with sufficient power to cause light that passes through to control the direction of other light, providing the switching capability, Sargent said. "This demonstration is a major advance in closing a gap" in how materials can be used to control light in optical devices, according to Mark Kuzyk, a physics professor at Washington State University. Kuzyk said materials studied previously could control only 3 percent to 5 percent of light. The new material approaches the theoretical limit of what is possible according to the laws of quantum mechanics, according to Kuzyk. "Once all-optical devices and systems become prevalent, electronic bottlenecks will no longer be an issue," he said. Superconnect's Lehenbauer agrees that "it's fascinating" to have material for an optical switch, but warns "it could be awhile until an all-optical network is possible." Lehenbauer said switches and routers must identify individual packets and route data intelligently, tasks that are not possible using a simple optical switch. "Unless you have an optical computer inside the switch to make these decisions, you'll still need electronic components." Lehenbauer said the technology would make sense in other applications focused on transmitting data. "It could be great as a super-fast optical repeater that regenerates a signal over long distances," Lehenbauer said. "The Holy Grail is to have an all-optical network," according to Paul Polishuk, president of network consulting company Information Gatekeepers. But obtaining it could also be a nearly impossible quest, Polishuk said. Polishuk said substantial research dollars were invested in optical switches in the last few years, but several companies abandoned their efforts because they could not develop devices durable enough to survive in a network environment. Polishuk also questioned the need for higher-speed networks. "Who's going to buy it when 40-Gb networks aren't getting off the ground?" he asked. Optical-networking company Infinera is taking another approach to boosting internet performance. The company has developed a photonic integrated circuit, a hybrid of optical and electronic technologies, according to Serge Melle, vice president of network architecture. Melle said the technology combines discrete functions into a single chip, and can transmit data at speeds of up to 100 Gbps. "People are doing in optics today what was done with semiconductors 40 years ago," Melle said.

Via:wired.com

|

RSS feed

RSS feed